Written by Sophie Kalkowski-Pope

Imagine the early morning trills of birdsong as you walk through a lush jungle garden to breakfast. Bordered by fringing reef and world class diving at your doorstep. And some of the most adventurous and international research teams congregating in this one location.

This is what it is like to stay at Walindi Plantation Resort, Kimbe Bay, Papua New Guinea.

Getting to a part of the world as remote as Kimbe is not always easy of course. After many delays and cancellations, and an overnight stay in Port Moresby, I finally made it to Walindi. The next day was surreal. Welcomed by Chenye and Ema, I quickly met the broader team and all the friendly staff.

Walindi was established by Max and Cecile Benjamin in 1983 and has been offering world class diving and research experience ever since. Established in direct partnership with Walindi, is Mahonia Na Dari, a research and conservation not for profit that has been operating in Kimbe Bay for 26 years.

Mahonia Na Dari (or guardians of the sea) hosts resident researchers dedicated to studying the biodiversity of the area, and also runs a variety of educational and outreach programs for local community school groups.

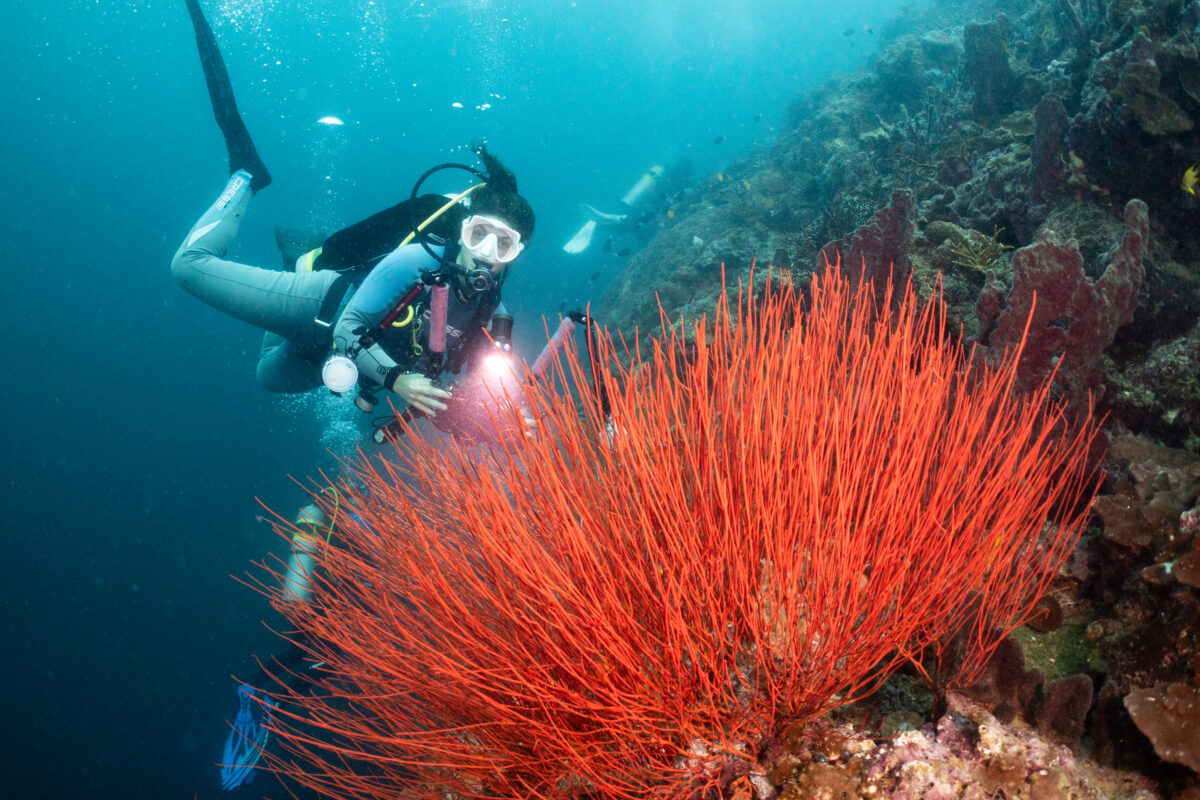

My first few days at Walindi were spent familiarising myself with my new dive gear and camera equipment. I was lucky enough to dive on the Walindi day boats, visiting a range of seamounts and continental islands. Picture huge drop offs plunging into the deep blue, the biggest gorgonian sea fans you have ever seen in your life, and trailing sponges hanging like vines from a jungle.

My favourite site by far was Bradfords. On the trip out, it was fine and calm; the kind of day where the water takes on that rich deep blue, and you know the vis is going to be fantastic.

After plunging into the water, I didn’t know where to look.

As we descended down on to the pinnacle, dark shapes in the distance became hundreds of shimmering silver bodies, schools of trevally zoomed past, against a backdrop of a cloud of circulating barracuda, while clusters of sweetlips hovered gingerly above the reef. It was incredible to be surrounded by so much life in the water.

I then had the opportunity to work with Melissa Versteeg, the resident researcher here at Mahonia Na Dari. Melissa is undertaking a 6 month stint of fieldwork here in Kimbe, and is using anemones and associated anemonefishes as a model system to study the effects of environment stressors on coral reef fishes with high site dependence.

Heading out with Melissa and her research assistant Marta, I learnt how to undertake benthic video surveys and observed how Melissa monitors her 104 anemones and their associated anemonefishes, including how to recognise various behaviours. It was magic watching Mel gently sweep up the side of the anemone to reveal a clutch of golden orange eggs, which the anemonefishes lay at the base of their host anemone, which she quickly recorded in her notes.

Besides monitoring both Amphiprion perideraion and Amphiprion percula, Mel also monitors environmental variables around the host anemone at a small scale, to see if variation between anemones plays a role in their resistance to environmental stressors or their recovery following environmental disturbances.

Things like the light available for photosynthesis, are important environmental parameters to consider, because just like corals, anemones contain photosynthetic algae (symbiodinium), which rely on light to produce food.

Moreover, because of this symbiosis with algae, anemones, like corals, can bleach when they experience high levels of environmental stress. I also learnt how to quantify PAR- photosynthetically active radiation, using a LiCOR sensor!

During her studies here, Melissa witnessed and documented the recent mass bleaching events along the inshores of Kimbe Bay, and the anemones’ subsequent recovery.

Water temperatures in the bay reached as high as 34C. Normal annual water temperatures range between 28-32°C, so the recorded temperatures were well outside of the thermal thresholds for anemones, which led to their bleaching.

One of the most interesting things I learnt during my stay was the unusual patterns displayed by anemones as they recover.

Like in this image, the colour gradually returns around the edges of the anemone, with zooxanthellae being absorbed gradually from the border.

It’s unknown why exactly this occurs but Mel and her colleagues believe it could be linked to differences in the types and location of zooxanthellae communities. Thank you Mel for taking me on board and for your enthusiasm in teaching and sharing knowledge!

I also had a chance to help Marta Panero with some data for her pilot study, looking at how gorgonian sea fans support fish communities and cryptic invertebrates. We spend the day measuring the absolutely enormous sea fans, and setting up video mounts to capture data about the surrounding fish life. Being surrounded by not just one, but a forest sea fans all 2-3 metres wide in size was just incredible.

Finally, while I was at Walindi, a multi-institutional team of Prof Geoff Jones’s research group from JCU and researchers from KAUST were in the field. The team has been running a long term study of anemonefish genetics in Kimbe bay, using the data to track connectivity and community structure. I joined them on one of their trips, and it was fascinating to watch their methods in action.

The team catches and releases all fish present on the anemone, right from the dominant female to the smallest recruit, measures each individual, and takes a small fin clip.

This sample of genetic material taken from their caudal fin is painless, a bit similar to clipping your fingernails. Afterwards, all the thousands of samples are carefully labelled, packaged and transported for sequencing back at the lab. Helping Jaan with his PhD project through OIST (Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology), I even had the chance to catch my first anemone fish, an Amphiprion clarkii, which was certainly more challenging than expected.

Thank you to Geoff, Maya, and the team for welcoming me on board!

Overall, my time at Walindi exposed me to some incredible research and diving opportunities. I cannot thank Chenye, Ema and Cecile for their generosity in hosting me. The friendly locals, incredible rainforests and wildlife, and remarkable diving really made this trip special.

The next stop on my scholarship year is visiting CCEF (The Coastal Conservation and Education foundation) in the Philippines to learn about community based MPA management.

I am so grateful to OWUSS for making opportunities I would not have dreamed of before and broadening my horizons to a global scale. A special thank you to the countless volunteers behind OWUSS, and the sponsors that make this scholarship possible at ROLEX. I would also like to thank my equipment sponsors at TUSA, Waterproof International, Reef Photo & Video, Mako Eyewear, my camera gear sponsors at Reef Photo & Video, Nauticam, and long time scholarship supporters DAN, and PADI.

To follow along on my adventures, I highly recommend you follow me on social media!

My Instagram @sophie_dives is where I post most regularly.

You can also contact me on LinkedIn, Twitter, Tiktok, and the Australasian Scholar Facebook Page.

You can also subscribe to this blog here!