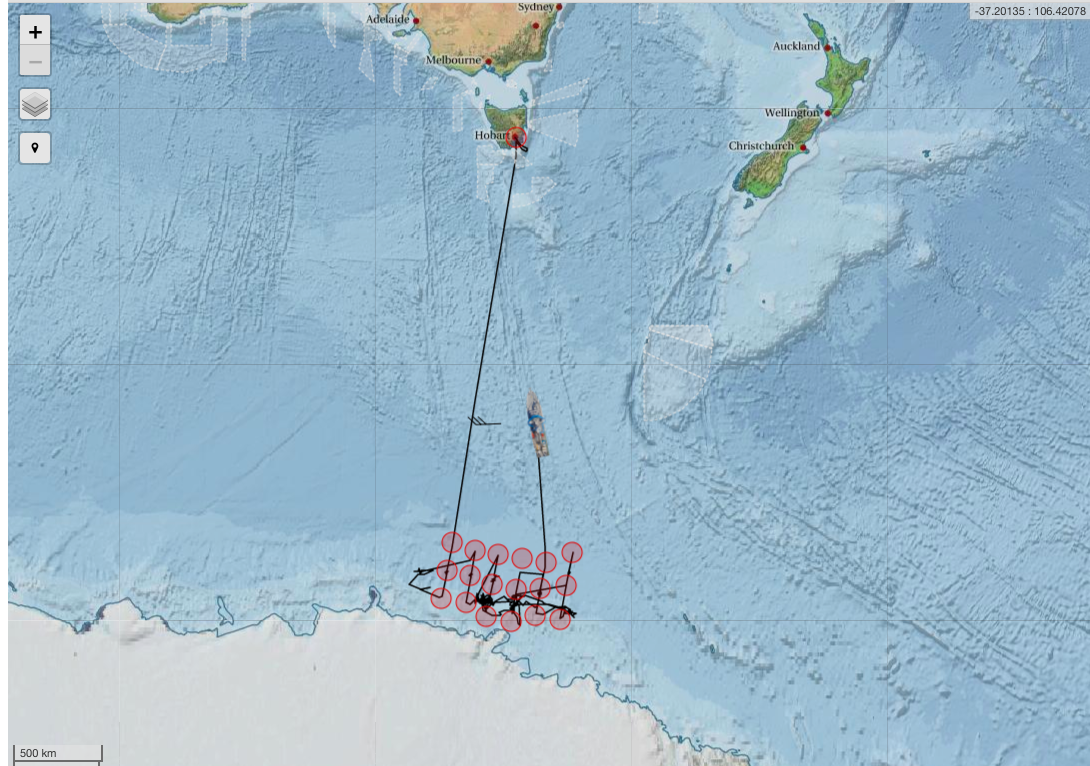

In January I set off on a 7-week voyage on the CSIRO Marine National Facility Vessel, RV Investigator as one of 28 scientists on the most comprehensive scientific study ever undertaken on the world’s largest animals, Antarctic Blue Whales and their food source Antarctic Krill. The voyage, led by the Australian Antarctic Program, was called the ENRICH Voyage, standing for ‘Euphausids and Nutrient Recycling In Cetacean Hotspots’ (note: euphausids are krill, cetaceans are whales). This voyage was made up of a number of different teams including the krill team, the whale observers team, the passive acoustics team, the active acoustics team, the trace metal team, the unmanned aerial systems team, the biogeochemistry team, as well as the media team onboard to film for an upcoming documentary series.

It took us approximately 7-days to reach our destination and the seas were rough to say the least on the way down. It took us all a few days to get our sea-legs!

The Voyage was led by Chief Scientist Mike Double, as well as Deputy Chief Scientist Elanor Bell. I would make up one of seven members of the Antarctic Krill research team, who was undertaking a range of research aims including for the first time on an Australian research vessel in the Southern Ocean, capturing krill swarms in 3D utilising state-of-the-art echosounder technology. Before this voyage, very little was understood about krill swarms and the types of swarms they form. All of this information helps to make better management decisions for an incredibly valuable food source to not only whales, but many of the charismatic (and non-charismatic) animals in the Southern Ocean.

And where we found krill we usually found whales… Antarctic Blue Whales almost exclusively eat krill. In one day, an adult blue whale can eat up to 4 million krill, more than 3 tonnes! In order for them to do this, they must feed in areas where they can find high concentrations of krill. Plus, iron has been found to be an incredibly important nutrient that is recycled into the ocean thanks to the influence of higher order predators waste, in particular, whale poo! Krill, whales, ice, poo – it was the perfect combination of elements that each of the research teams had their own questions they aimed to answer over the 7 week period.

I will focus on what I was helping to achieve in the krill team, but more information about what each of the teams were researching can be found by following the hyperlink http://www.marinemammals.gov.au/research-and-activities/antarctic-blue-whale-and-krill-voyage-2019/voyage-news/successful-voyage-returns-from-southern-ocean.

The krill team was split into a day and night team (I was on the night team), as we worked around the clock to understand the patterns and behaviours of Antarctic Krill, Euphausia superba. On our way south, and on the way home north we towed a CPR, also known as a Continuous Plankton Recorder. This piece of scientific equipment has remained largely unchanged since its original design in the early 1900’s, and is one of the longest running marine biological monitoring programs around the world. The CPR works by filtering plankton from the water over long distances (in our case 450 nautical miles) on continuously moving bands of filter silk. This then gives us a sample representing each of the plankton groups (both zooplankton and phytoplankton) over a continued period of time – ingenious! This process is conducted on every voyage south by an Australian vessel.

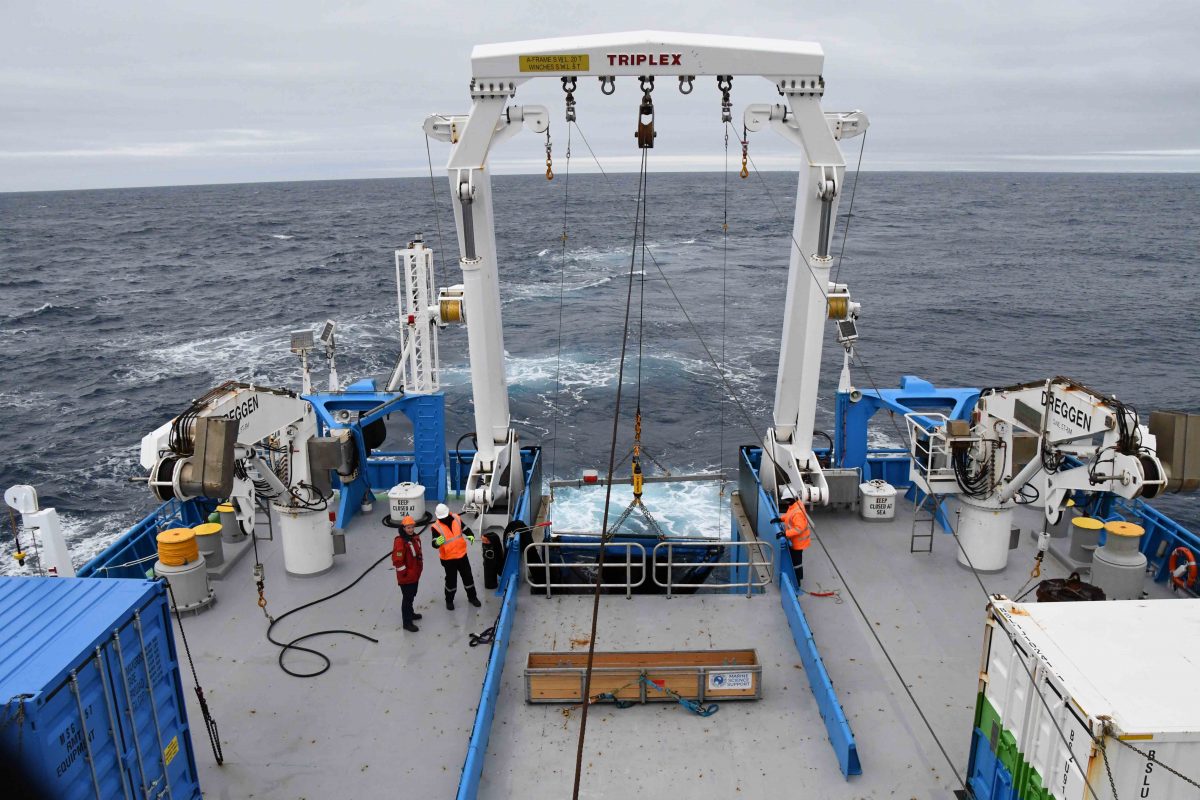

Once we hit south of 60 degrees, we were on the hunt for krill swarms. We would be deploying a net, known as the RMT (Rectangular Mid-water Trawls), where we would take a sub-sample of a swarm, to have a better understanding of the biology of the animals that made up that swarms. Joshua Lawrence, the acoustician onboard, used the multibeam ecosounder to help direct us to the swarm to take a sample, as well as ‘paint a picture’ of the size, shape and density of krill swarms that were being observed in three-dimension.

The RMT was made up of two nets, with two different cod-ends attached. The RMT 1 was the smaller cod-end which had a finer net-sized mesh attached and took a sub-sample of the phytoplankton that was in the area of the ocean we were in at the time, which is an important factor in understanding how the krill swarm might be behaving (are they feeding, or are they hunting for phytoplankton?). The other cod-end was the RMT 8, which had a larger sized net-mesh, which we were aiming to catch zooplankton in, preferably krill! The RMT also had a multiple CTDs (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) attached to it as well.

With the help of the crew onboard the ship, the net was lifted with the A-frame and deployed into the water. Through a communications system, the krill team would ask the crew to lower the winch line to a defined depth, depending on where we were observing the krill swarms on the ecosounder. Once the net was at the depth we believed the swarm to be at according to what we were reading on the instruments. Whoever was in charge of the trawl, would ask another team member, to open the net, whereby we would send a command, through a doppler system, which would let the net know when we wanted it to open or close according to the command that was sent.

If we were successful, we would catch krill! We were only aiming to take small samples of the krill, which we were using for multiple purposes. This included biological samples that were snap frozen for genetic and further analysis back in Hobart. Collecting gravid female krill (female krill full of eggs) in order to capture the fertilized eggs. We would be rearing the eggs through their multiple larval stages, bringing them back to Hobart to the Australian Antarctic Division where experiments would soon be undertaken, aiming to get a better understanding of the influence of increasing CO2 levels on the larvae. This is an extremely important question considering this is the future we are currently facing and because of the fundamental role krill play in the ecosystem and food-chain.

Additionally, we would undertake a total of 20 IGR (Instantaneous Growth Rate) Experiments on, led by Jess Melvin. This involved putting 288 individual krill into their own jars, over a 4-day experimental period, checking the jars every 12 hours to see if the krill had moulted. This process, seen in all crustaceans, occurs approximately every 10 – 30 days over the summer months in Antarctic krill, and can occur due to many reasons including growth or stress. Jess had conducted her Master’s dissertation on this study and aimed to show there was a significant difference when Antarctic krill moult, particularly after a gravid female expends her eggs. Krill are incredible animals that are known to be able to grow and shrink depending on their environmental conditions and food availability.

After the 12-hour checks we would remove the krill that had moulted from the experiment and measure their carapace size (both of the live animal and of their exoskeleton), as well as their uropod length (their little tails – again both live animal and exoskeleton), to understand patterns and differences in the moulting processes. During this analysis, each individual was sexed so we could identify at what stage of their life cycle they were at (for example a gravid female or a female who had just expended her eggs).

If you follow this link you will be able to see a video of the krill team in action working in the lab after catching some live krill: https://www.facebook.com/AusAntarctic/videos/621526248301086/

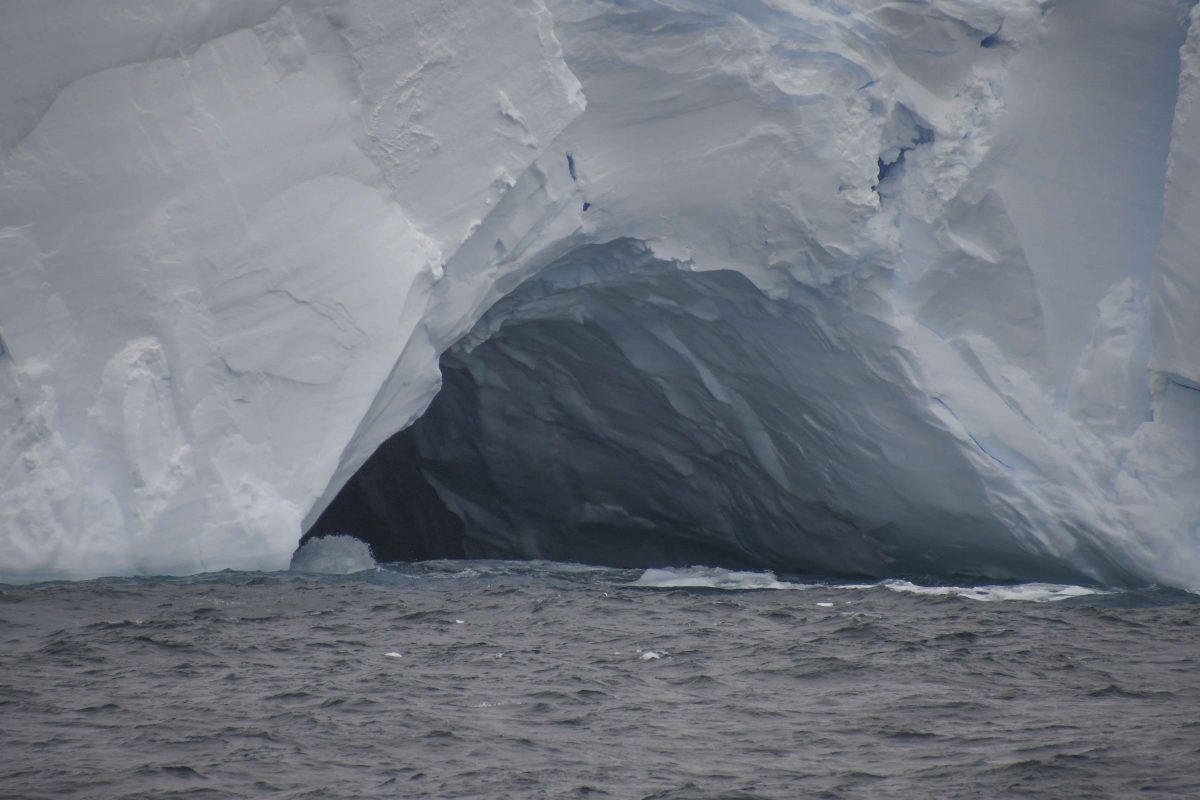

When we were not busy in the lab, we also got out on deck as much as possible so we could take in the incredible views of the icebergs and see the array of wildlife the Southern Ocean and Antarctica has to offer. It didn’t matter what time of the day it was (whether we were supposed to be asleep or not), when the ship encountered its first group of Antarctic Blue Whales, every single person was out on deck. It was an incredibly memorable experience to say the least and were lucky enough to have 3 enormous Antarctic Blue Whales right next to the ship. They even swam under the bow – it was just insane!

We were lucky enough to come across pods of Type C Killer Whales, as well as pods of Fin Whales, the second largest whale in the world, surface feeding.

Another delight, which was a phone call to the room whilst we were fast asleep was a large group of Humpback Whales surface feeding!

I couldn’t have asked for a better team to work with and learn from during my first voyage south to Antarctica. Working with world leaders in krill ecology and research including Dr So Kawaguchi and Rob King was an incredible honour, and I feel extremely privileged to have been part of this incredible scientific voyage.

This video summarises what all teams achieved over the seven-weeks brilliantly and I highly recommend watching this:

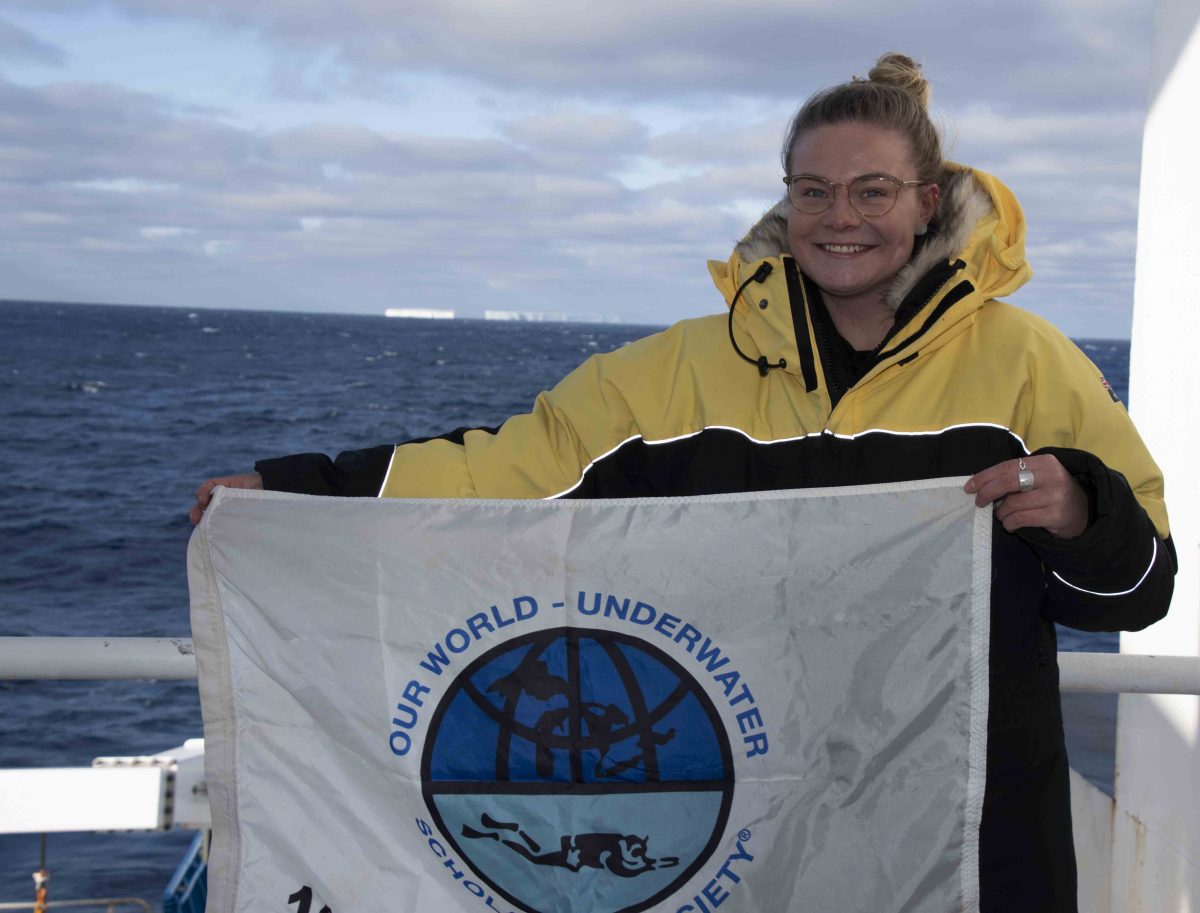

I may not have got to dive during this time, but thanks to the biogeochemistry team, I also got to attach the OWUSS flag to the CTD before they were conducting deep water sampling at 2000 meters – meaning flag 14 got a deep dip, even touching Antarctic Bottom Water!!!

I cannot thank Kerrie Swadling and So for asking me to come onboard as a krill researcher and participate in world-class science. A huge thank you to Mike and Elanor for leading such an incredible 7-weeks of science. I’d also like to thank Rob, Jess, Haiting, Josh, and Maddie for all the brilliant times we had in the krill lab and the non-stop laughter! Thanks to one of my best friends Abbie, who was conducting her PhD research onboard, for putting up with me in a room for 7-weeks! To every other ENRICH team member, thank you for inspiring me as an early career scientist about the incredible research that is happening, and for opening my eyes up to a whole new world.

In particular, thank you to CSIRO Marine National Facility and all the crew onboard for keeping us warm, well fed, and getting us to and from Hobart safely, and to the Australian Antarctic Program. Additionally a big thank you to Chris Dalton and Nikon Australia for allowing me to use an incredible piece of their equipment to capture these once-in-a-lifetime moments with. As always, a big thank you to those who continually support my scholarship year: OWUSS, Rolex, TUSA, Waterproof International, DAN, PADI, Mako Eyewear, Reef Photo & Video and Nauticam.