A column of mist pierces the horizon, followed by a deep unearthly ‘fwisssssh’, as if the ocean itself has come up for air. A large dark shape slides through the ocean. Its body slicing through the waves. It lifts its tail out of the water. This creature that we call whale has incredible origins. It has an incredible evolutionary path it has taken. The journey to become a whale was long and complex. To understand why cetaceans fascinate me so much, I need to tell you their evolutionary tale first.

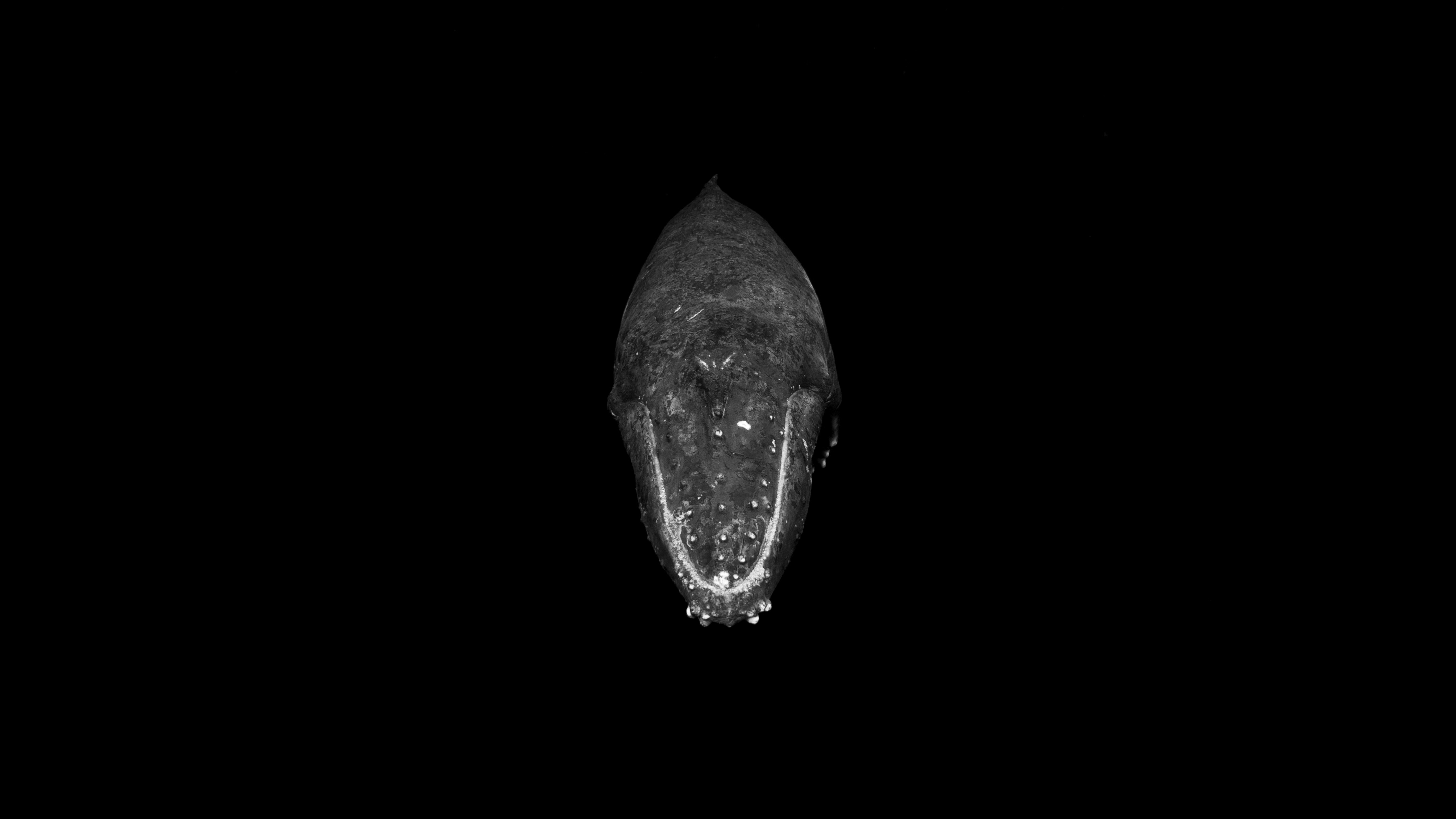

Photo by Melinda Brown

Lets step back 50 million years ago. The planet is warmer, and mammals dominate the land, while birds rule the skies and sharks and fish flourish in the ocean. At the oceans edge lives a goat sized creature called Pakicetus. It is the earliest cetacean. Over the next 10 million years, Pakicetus will evolve dramatically. It’s back legs will disappear, it’s front legs will become large flippers. It’s nostrils will migrate up it’s skull to become the blow hole we recognise now. It will feed only on sea creatures. It will even nurse it’s young in the sea. In just 10 million years this small mammal has become an ocean giant. It will return completely to the sea.

I find whales both paradoxical and puzzling. I don’t know whether it is because of the fact that they are incredibly familiar and yet completely alien. I identify with their intelligence, sociality and sentience, yet they live in a foreign world. One that is cold and dark, one that is hostile to humans. One that we know nothing about.

Photo by Melinda Brown

With an interest in ethology, the study of animal behaviour, cetaceans excite me the most. With their quick evolutionary journey back to the sea, I’ve always thought that their behaviour has been very purposeful. With climate change well and truly upon us, I wonder how these incredible animals will continue their path of adaptation and evolution. How will their forced journey back into warmer waters affect them? Surely, we will lose the mysticetes, the baleen whales. They feed on krill and small fish, and as the sea ice melts, their main food source, krill, loses its habitat. They will lose their food due to climate change. They will starve and die unless things change. Or they adapt. But can they adapt? Is their behaviour changing? Are their migratory routes becoming longer or shorter? Are they having more or less young? If only they could talk and tell us. The odontocetes, toothed whales, they will adapt. We are already seeing signs of it. They can switch prey, they can hunt. If they are quick they can learn to change their diet, their predation techniques, their culture so to speak.

And this fascination, these questions, led me to Scott Portelli in Tonga. Scott has over 1000 days on the ocean in Tonga. Over 1000 days with Megaptera novaeangliae; the humpback whale. As a photographer, Scott has captured some incredible moments with these giants, and his knowledge and stories of their behaviour is invaluable.

Photo by Melinda Brown

My first day on the water with Scott was an ocean of emotions. I was so incredibly excited, yet so nervous. I didn’t know what to expect. As the boat drove out of the harbour and into the ocean my heart was racing. I was looking for that first blow, the tell-tale sign of the whale. We came across more than one blow. It was a heat run. A group of rowdy males were chasing a female in the ultimate test of endurance and persistence. The female would mate the strongest and toughest male. The one that could out last the rest. Believe it or not, whales can move quite fast, and be incredibly aggressive during a heat run. Our skipper Sione expertly moved the boat into position as we stood with our masks and fins on, cameras in hand, ready to jump at any moment.

“NOW, SCOTT NOW” yelled Sione.

I jumped in after Scott, leaping into a whales world. The males rushed past us, pushing each other, but completely and utterly aware of our positions, they manoeuvred around us gracefully as we tried to keep up with them. There was no time to cry tears of joy, no time to think about what had just happened and how happy I was. We were swimming hard to keep up with them as they rushed past us. Scott powered ahead as if he was actually part fish (I’m still convinced that he might be). We gave up after a few minutes and jumped back into the boat, ready for the next drop. I didn’t have much to say, I think I went a little bit catatonic after that first moment. The implications of those first few minutes with the whales wouldn’t hit me until much later. My mind had been made up for me. I was hooked.

Photo by Melinda Brown

Later that day I witnessed Scott’s understanding of whale behaviour. Working with the skipper’s endless knowledge of the whales, we moved into position with a mum and calf, and Scott jumped in to check it. Scott slid gently into the water, and approached them silently. He floated near them, not too close, but enough to let them know he was there. They stayed. He moved closer, they stayed again. His hand goes up, but he doesn’t look up. He is watching the whales, watching their behaviour. We copy Scott, sliding into the water and moving to his side, just as the young whale stays by its mother, we stay with Scott. The calf is only a few weeks old. Curious and inquisitive. It looks up at us from under it’s mums pectoral flipper. It comes out further, closer, edging towards us as we wait with anticipation. It breaks free from it’s mothers touch, and floats to the surface metres from us. It rolls, eyeing us. There is something truly incredible about a whale’s eye. Without anthropomorphising them, they appear to be incredibly aware of what we are. They appear to know us, to show curiosity and interest towards the humans in the water. Whether this is true or not we will never know, as it is completely unfair to place human attributes and emotions onto a creature that may not experience any of them. But that’s all part of the sense of connection we share with whales.

Photo by Melinda Brown

Scott knows these whales so intimately that our encounters with them could often last for hours without the whales moving away from us. Some people express concern that swimming with the whales interferes with their daily lives. The whales have the entire ocean to dive into if they wish to leave us humans, but more often than not, they don’t. They stay, they let us look. We experienced this multiple times with mothers and their young. One of the most memorable times for me was when we came across a mother, calf and a male escort. The escort was singing. He was floating ten metres down underneath us, a few metres from the side of the mother. His song echoed through the ocean, rumbling as he repeated his verses and chorus, reverberating through our bodies. You could feel it. Physically. It shakes you to your core. It makes you listen, really listen. Everyone was so quite in the water for those few hours, listening to the predictable yet haunting song, watching the calf surface, swim around us, then return to it’s mother, while we floated trance-like, cameras in hand, reverent of these ocean giants and the space they shared with us.

Another moment that will always remain precious to me was when we encountered an incredibly large female ‘canoeing’. She was hanging vertically in the water, tail out, catatonic. The Tongans call them canoe whales because of how the tail, or fluke, look from a distance. You could easily mistake them for a canoe. We spent two days with this girl. We thought she might have been pregnant. Whale birth has never been documented, so nobody knows whether this behaviour could be signs of labour, or if it’s just a comfortable way to float for her. She hung, eyes shut, as we swam on the surface around her. The size of her tail was unfathomable, casting a giant shadow over us as we looked up at it in awe. This girl was very tolerant of us. She would let us swim around her, even down to her pectoral flipper, but never past eye level. We would dive, she would watch us, waiting to see how far we would go. Past the flipper, down to her eye; her flippers move, a warning. Stop she says. No further or I’ll move away. It’s all insinuated in the body language. Scott watches her, and tells us no further than her eye. We all watch for that movement, we don’t want to make her uncomfortable. We know our boundaries with her now. We spent many hours with this female, and every one of those hours was life changing.

Photo by Scott Portelli

Whilst photographing this female, we all took many photos of her incredible fluke that hung over us. A whale’s fluke is the equivalent of our fingerprints. Each is unique, and remains nearly unchanged throughout it’s adult life. Fluke photos collected during our days on the water were then added to the Tongan Fluke Collective. This is a project created and run solely by Scott. I was lucky enough to help him with this during my stay, and assisted with cataloguing and organising flukes. Scott makes the images and information about them available to the public for free through dropbox. He believes in sharing data, something that some scientists struggle with in this competitive day and age. These images are used by organisations all over the world, and one in particular (Happy Whale), provides a lot of insight into the elusive lives of these whales. By submitting flukes to this database, whales are able to be tracked from all over the world. Happy Whale would use these images in conjunction with images from Antarctica and other countries to map the whales route to Tonga. Not only does this show migratory routes, it can help scientists get a rough estimate of age if an individual is sighted consistently throughout its life. Being able to help with this catalogue and contribute to the science behind cetaceans was an incredible opportunity, and I can’t thank Scott enough for trusting me with that job whilst I was there.

Photo by Vili Takua

The more I try to describe my time in Tonga, the more I realise words will never do it justice. I learnt so much in regards to whale behaviour, and I have developed an incredible respect for people like Scott Portelli who dedicate their lives to documenting these animals. This trip has truly set my path for the rest of the year. Cetaceans have stolen my heart, and I can’t wait to pursue them throughout my life. Thank you to everyone who made my time there incredible, especially Phil who runs Whales in the Wild for providing the excellent boats and crew that Scott charters (also thanks for all the ‘dad’ jokes), Vili and Sione for being incredible skippers, Roanna and Stefan for the constant good vibes and adventures, and of course Louise, Poo-wen, Josef, Joe, Olivier, Eduardo and Anthony for sharing these experiences with me on board ‘No Bananas’. I am so incredibly grateful for this month of my life. Scott Portelli, words can’t describe how much you’ve changed my life in such a short time, and I can never thank you enough for sharing your time and knowledge so generously with me.

Photo by Vili Takua