Written by Millie Mannering

Over my scholarship year, I have witnessed first-hand how interconnected people are to the ocean, across the globe. In fact, these deep rooted connections have been evident throughout history.

The importance of coupled human-ocean systems was emphasised during my time with the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and Senior Shellfish Biologist, Julie Barber. I learnt how Indigenous communities have displayed environmental stewardship and managed resources since time immemorial. An example of this is through constructing clam gardens, an ancient form of aquaculture that are evident throughout North America’s Pacific Northwest.

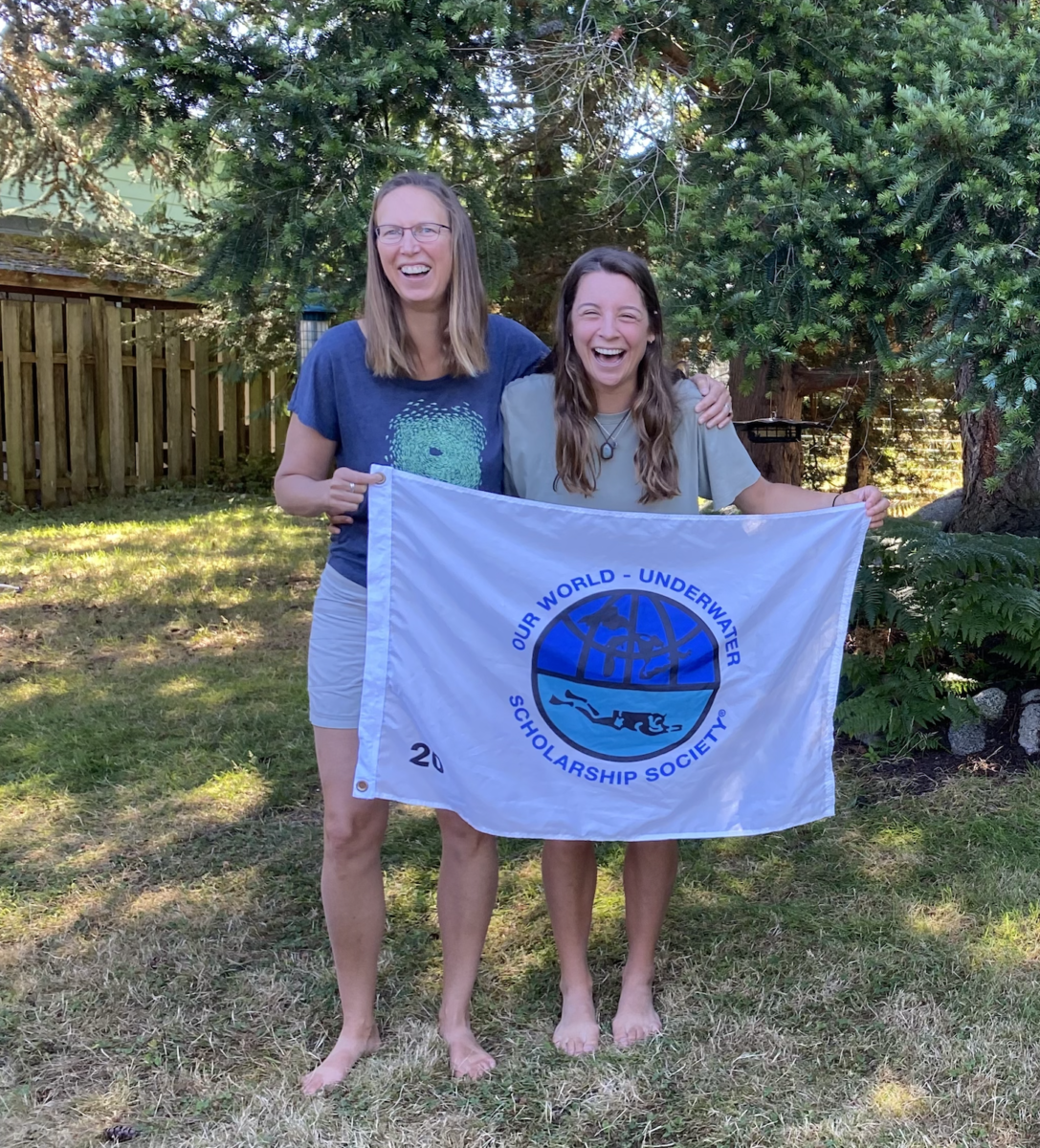

Senior Shellfish Biologist, Julie Barber, with Millie Mannering.

Clams are a culturally important and protein-rich food source to First Nations and Native American people. These bivalves are easily harvested in the intertidal zone. Clam gardens are a form of environmental engineering and an ancient, Indigenous practice used to increase shellfish production. Rock walls built on the intertidal zone modify the beach by reducing the beach slope gradient through trapped sediment, subsequently increasing the optimal tidal range where clam populations thrive.

Left: Conducting suveys of wild clam populations within the tribal fishing grounds to estimate biomass and determine sustainable quotas for tribal and state fisheries co-management.

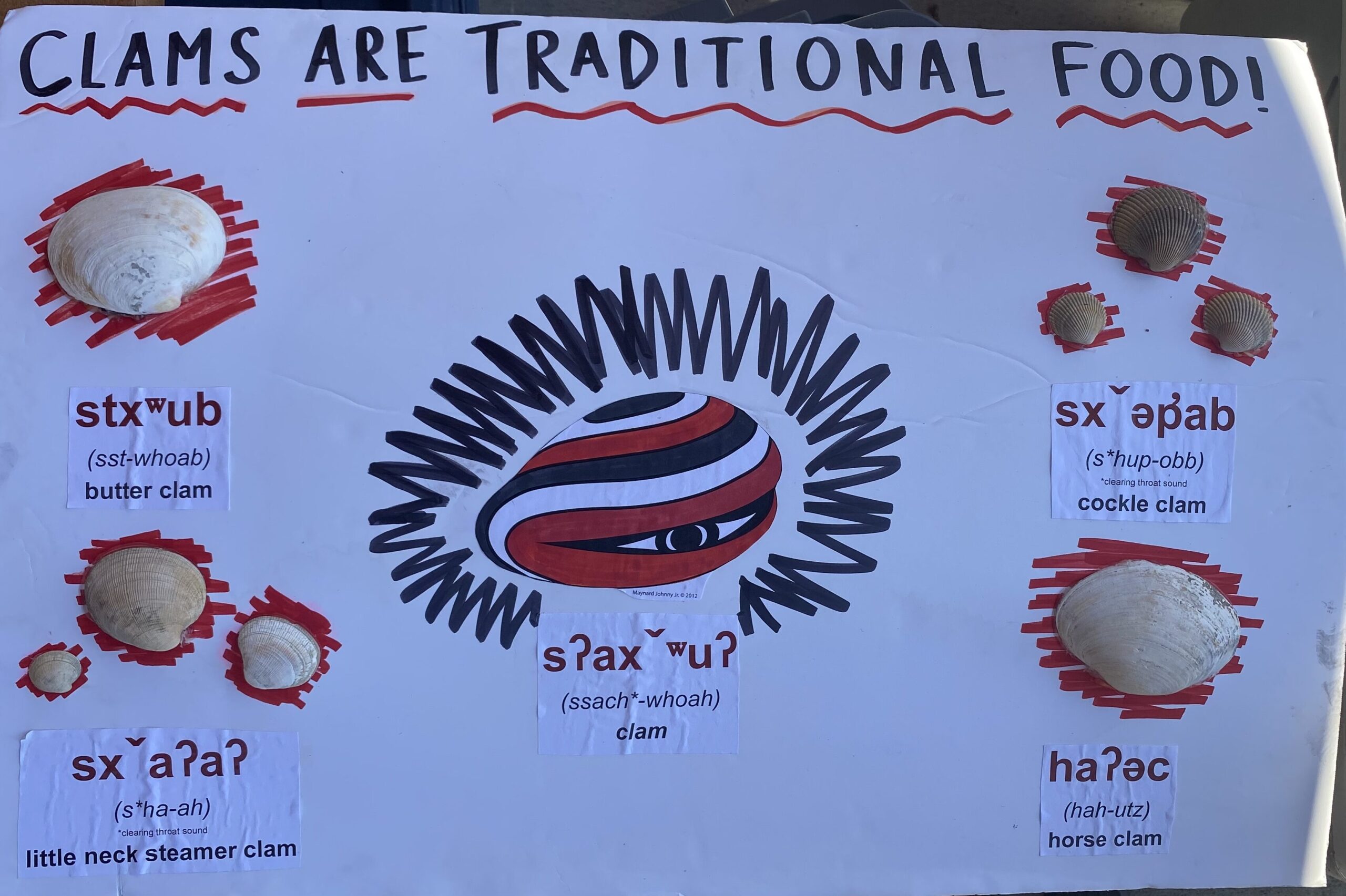

Right: Clams are traditional food! Traditional food is an Indigenous ocean connection shown in our own cultural importance of gathering kaimoana (seafood) in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Credit: Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

Indigenous communities built and cared for clam gardens as this early mariculture technology increases clam biomass and density in the area, subsequently building food source reliability. To care for these gardens, traditional knowledge holders explained to me the process of regular digging in the gardens, removing boulders and algae as well as adding broken shells back to the area. These processes boost recruitment through oxygenation and improved sediment conditions, increasing the productivity of clams and other marine organisms within the gardens. However, like many cultural traditions, the Indigenous practice of clam gardening was almost lost with European settlement.

Working to lay the stones to create the clam garden. Lifting and placing the 33 tonnes of rock was tough on the arm muscles but we worked hard and efficiently together. Photo: NWIFC

Working together to build the clam garden wall on a beautiful day at Kiket Island. Photo: Julie Barber

In a historic moment, the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community built the first modern clam garden in the USA at Kukutali Preserve, Kiket Island. It was such a privilege to be involved in this significant and sacred day. Reviving this ancient aquaculture technique from thousands of years ago, we lifted 33 tonnes of rock needed to create the wall. It was empowering to see the restoration of tradition and culture among Coast Salish people.

Traditional food is an integral aspect of Coast Salish people’s lives and I found it fascinating to learn about their customs and values. The clam garden is a method to build food security in the face of climate change and protect these ocean resources for future generations. Most importantly, this event was the revitalisation of an ancient Indigenous tradition and revitalisation of Coast Salish people culture.

Julie Barber and Millie Mannering on top of the newly built clam garden wall.

Jay Dimond and Millie Mannering very stoked having completed their dive at Deception Pass. Loving my first drysuit-tub washing experience for efficient removal of saltwater. Photos: Jay Dimond

Whilst in Anacortes, Washington, marine biologist Dr. Jay Dimond took me to tour the Western Washington University’s Shannon Point Marine Center. I enjoyed listening to the Research Experiences for Undergraduates student symposium, and was impressed by their thorough research presentations. Jay also took me for a dive at Deception Pass, notorious for high currents and spectacular underwater life – it was awesome!

5 OWUSS Scholars reunite in Anacortes! One of my favourite aspects of the scholarship year has been the opportunity to meet alumni from the Society and connect with awe-inspiring women. From left: Millie Mannering, Julie Barber, Ana Sofia Guerra, Neha Acharya-Patel, Megan Cook. Photo: Jay Dimond

I am immensely grateful to the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community for sharing their knowledge, culture and way of life with me. Thank you to Julie Barber and Jay Dimond for your kindness and hosting me so generously. Many thanks for showing me your beautiful home, shredding the mountain bike trails and creating the most incredibly delicious meals!

As always, a huge thank you to the many, kind people who continue to support me throughout the scholarship year. Thank you to the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society and Rolex for making the scholarship possible. I would also like to thank my equipment sponsors Reef Photo and Video, Nauticam and Light and Motion as well as TUSA, Waterproof, Tabata Australia and Suunto.

Trip Tune: Wandering Eye – Fat Freddy’s Drop

Top Tip: Follow the deer to find the best wild berry patches

Join me, above and beneath the surface, on my adventures throughout the scholarship year. Subscribe to my blogs, follow along on Instagram, Facebook or flick me an email! Next, I’m heading up the coast to explore more of the beautiful Pacific Northwest ..

References:

1. Deur D, Dick A, Recalma-Clutesi K, Turner N (2015) Kwakwaka’wakw “Clam Gardens”. Human Ecology

2. Groesbeck AS, Rowell K, Lepofsky D, Salomon AK (2014) Ancient Clam Gardens Increased Shellfish Production: Adaptive Strategies from the Past Can Inform Food Security Today. PLoS ONE