Not all scholarship experiences are created equal. The beauty of the Rolex Scholarship is the variety of conditions and experiences you can find yourself in – from cage diving to freediving, crystal clear waters, tropics, waking up to icebergs, zero visibility, and even nowhere near the water at all. Today I’m going to share with you an experience that, despite seeing me out of the water for two whole weeks, was easily one of the most eye-opening of my year.

I left you at the end of my last blog with the cliff-hanging wrap-up (I hope) of a unique opportunity to join 2015 European Rolex Scholar, Danny Copeland, in the Azores Islands to help create a 360 degree Virtual Reality film about the mobula rays of Santa Maria, in attempts to save the world (mobulas). Fast forward a few weeks and I was in Johannesburg, South Africa. More than 500km away from the nearest coastline, I found myself in the deep end of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species 17th Conference of the Parties (CITES CoP17) – one of the most important conferences for wildlife conservation in the world.

Every three years, delegate parties from voting nations come together at CITES to discuss and vote on regulations in the trade of wild flora and fauna. Despite the spotlight often placed on issues in terrestrial species such as the trade of elephant ivory and rhino horn, the importance of managing trade of marine species has gained increasing focus in recent years. In 2013, CITES made history in marine conservation by voting yes for international protection of manta rays and five species of sharks. This year, with more than 180 nations and over 3,500 people participating in the largest CoP yet, that momentum continued with proposals to list silky sharks, three species of thresher sharks, and nine species of mobula rays on CITES Appendix II.

Targeted by fisheries to supply the shark fin and gill plate trades, these species have experienced documented population declines of over 70%, and therefore require global protections to ensure that international trade does not threaten their survival. For long-lived species with low reproductive output, such as the silkies, threshers and mobulas, this is especially critical. Under CITES, this Appendix II listing places restrictions on the international trade of these species, such that countries wishing to continue to trade must ensure that practices do not threaten their survival.

However, when it comes to CITES, the reality is that the fate of this vote lies in the hands of political delegates that are likely not scuba divers and may have never seen a mobula ray, let alone understand the threats they face. People will only protect what they care about, and they will only care about what they understand. So how do you encourage individuals to protect something they know very little about?

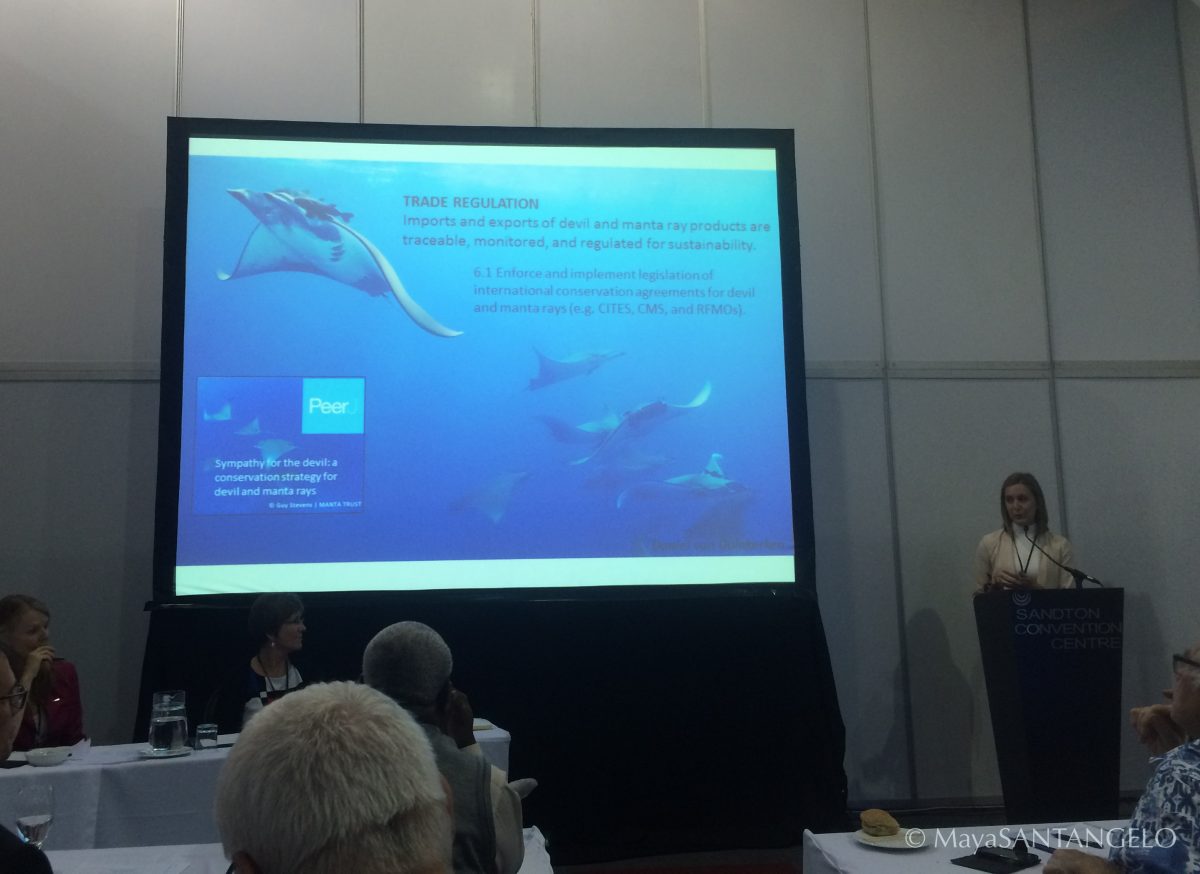

Joining a team with non-profit charity, The Manta Trust, I had the privilege to be involved with a unique media campaign initiative focused on this exact goal. With the idea to visually demonstrate to the CITES Parties why something should be protected, rather than just statistics on paper, this approach was taken a step further by using 360 degree Virtual Reality technology to bring media to the frontline of wildlife conservation. While we could not take all the voting delegates of CITES on a dive with the “mini mantas” of the ocean, virtual reality allowed us to bring to the conference the next best thing.

Watch the 360VR film below!

Over two weeks of marathon discussion with individuals representing everyone from voting delegates, to media networks and local visitors, we were able to take people from over 50 different nations on a virtual dive with the mini mantas of the Azores. By introducing them into a completely immersive experience, the virtual reality film was the perfect way to open the door for conversation to educate the delegates more about what they were voting on. Using virtual reality, we were in a unique position to show people how they can connect with these animals. Showing what it’s like to dive amongst mobula rays, people were exposed to the idea that if we don’t offer these animals some kind of protection, other people may not get to experience that at some point in the future.

Throughout the convention, the film not only became a highlight must-see for many attending, with individuals telling their colleagues, it was a clear testament of just what kind of impact a simple media story can have on educating and inspiring people to want to learn more about something.

As well as joining the Manta Trust team on this unique initiative, I also took the opportunity to attend CITES to foster my understanding of the realities and inner-workings of marine conservation on a global. Since learning to dive 11 years ago, the ocean has exponentially grown to become a bigger part of my life than I ever imagined, and it has been a natural evolution to develop a desire to give back. With an interest in marine research that can specifically be applied to conservation, I came to CITES wanting to gain an understanding of what it takes to protect a species – what research do policy makers need to make these decision? How is science applied in the management and enforcement of conservation policy?

By coming to CITES, I was given first-hand exposure and insights into the world of conservation politics. Over the two week period, I was able to observe the intricacies and learn what it takes to inform and educate these critical management decisions. When not helping present the film at the Manta Trust stand in the exhibition hall, I was able to attend side events involving informative presentations and discussions by sponsoring nations of the proposals, as well as international NGOS and renowned researchers, about what these species and CITES listings mean (not just for the nations, but for the world), why we need the help of CITES, and what will make these steps in conservation successful.

The pinnacle of the challenging, stressful and eventful conference came on the evening of the second last day, when the moment arrived for decisions of the proposals for the marine species in the plenary room. The chair addressed the 183 nations with the details of the proposals to list these species on Appendix II, and opened the floor for discussion in favor and against the protection of these species. It was inspiring to hear the words of support ring around the room from various nations – from those with large fisheries, to those that relied on ecotourism of these species – but also interesting to hear those still in opposition to the idea. All in all, things were sounding good for our elasmobranch friends – but this is a numbers game, with a two-thirds majority of votes required for a decision, and nothing is over in this conference until the chairwoman sings (speaks).

One by one, the moment for each proposal came, and we waited in white-knuckle suspense for 30 seconds as nations secretly cast their votes. First, the silky sharks, the most uncertain of the three. Passed. A huge, collective sigh of relief passed over the room in surprise of this initial success. Second, the thresher sharks. We crossed our fingers, hoping the first win was not just a fluke. Passed. Another sigh of relief. Finally, the mobulas. This was it – the big one, the one we had all worked so hard on, and the one we felt had the strongest support. Together, we took a deep breath to await the final blow.

‘No’ votes – 20. ‘Yes’ votes – 110.

The overwhelming success was met with a unified celebration all around the room. We did it.

With recognition from nations ranging from those with large fisheries, to those where ecotourism is critical for the economy, it was truly inspiring to see the support for these marine species at CoP17, as delegates voted overwhelmingly in favor of listing all 13 species of sharks and rays on CITES Appendix II. This listing means that governments around the world will now have to act to ensure that all continued trade in these species is legal and sustainable.

But what does CITES mean? Perhaps the most interesting lesson I was able to take away from this was in learning that, while CITES is an important step in conservation, achieving this protection does not mean the job is done.

The decisions made at CoP17 open up several interesting and important doors for conservation. In many cases, these species that are in need of our help in the form of international protection are considered to be “data deficient”. These new listings for marine species provide opportunities for data collection critical for effective conservation. With successful new CITES listings, the need for sound scientific research and understanding is essential now, more than ever, for effective management and implementation. The better we understand these elusive animals, the better we can enforce management to ensure their populations thrive into the future.

It is clear that conservation is becoming an increasingly recognized priority worldwide. As divers, underwater explorers, and ocean advocates, we have a unique opportunity to make our voices heard for the creatures we love to see, and support actions by governments and NGOs to ensure this momentum continues in a positive, forward direction.

This experience attending CITES was not only a great privilege to be part of the growing awareness and support for protection of marine species, it was hugely eye-opening to the realities of conservation politics. From presenting the film with Danny and Team Manta Trust, to observing side events and engaging in discussions about implementation for successful management, I was able to gain valuable exposure to and appreciation for the values and roles of media, science and legislation in this intricate web of conservation. Further, I was able to learn what CITES means in the grand scheme of things, and what lies ahead in the conservation of these animals and our oceans. Looking ahead, I am excited thinking about how I may be able to contribute in the future.

A huge thank you to Danny and The Manta Trust for letting me be a part of this unique campaign and massive eye-opener into the world of marine conservation. To Jorge Botelho and Manta Maria Dive Centre in the Azores for making the film production possible, and also a big thank you to Ana Sobral, David Diley, Shawn Heinrichs and all of team Manta Trust for all the brilliant learning experiences in conservation research and media, and for making the challenges so rewarding and fun. Here’s to a future filled with cooperating cameras, wildlife, and exciting conservation goals!