5 minute read

In January 2025, I set off on a long-awaited journey to a marine ecology lab I had admired for years. My first encounter with their work was at a fish conference in New Zealand, where I listened to their talks with fascination. It was the first time I had met marine scientists working in the country where I was born. Despite the geographic distance and differing cultures, our scientific interests overlapped. We asked similar questions, used the same technology, and pursued the same conservation goals in different contexts.

Dr. Alejandro Perez-Matus leads the Subtidal Marine Ecology Laboratory (Subelab) at the Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas (ECIM)—a marine research station perched on a stunning coastal cliff in Chile. I was fortunate to spend three weeks at ECIM, an experience that felt like an absolute dream. The research station was a hub of marine science, home to various labs investigating everything from oceanography and invertebrate morphology to fish biology and kelp restoration.

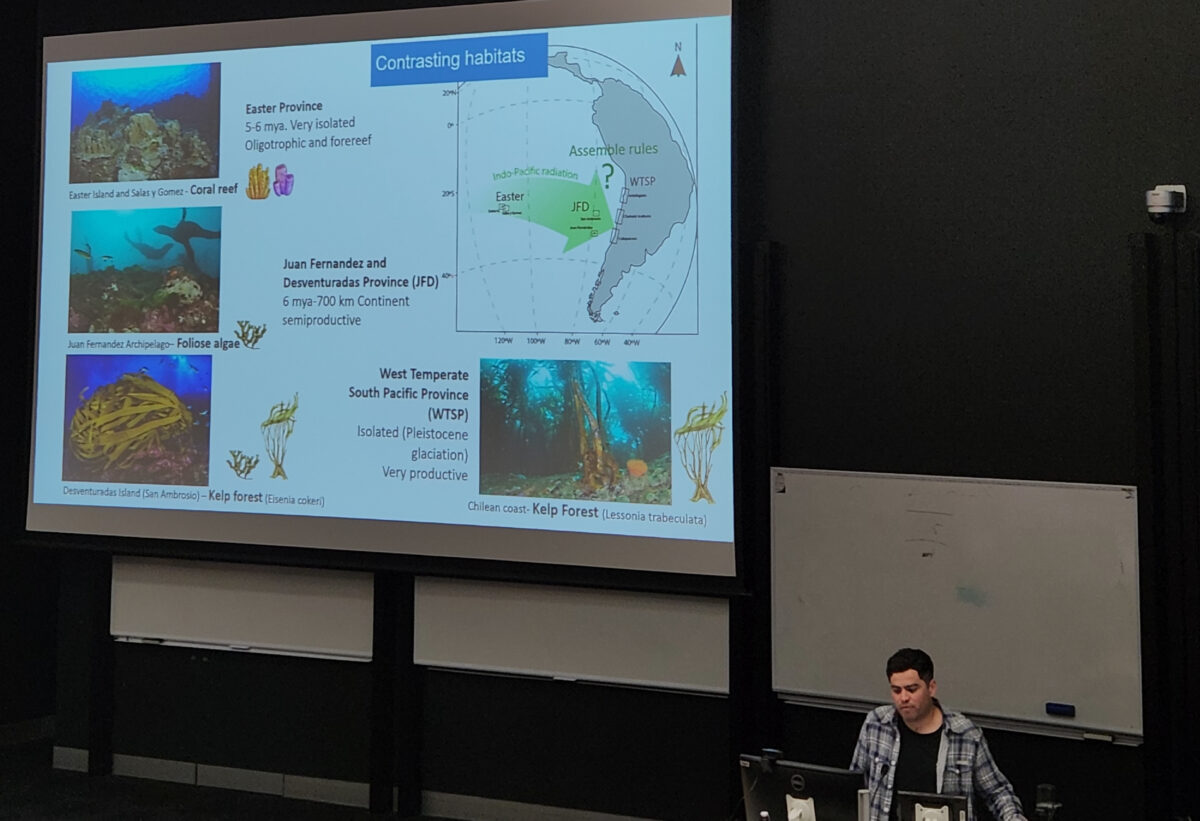

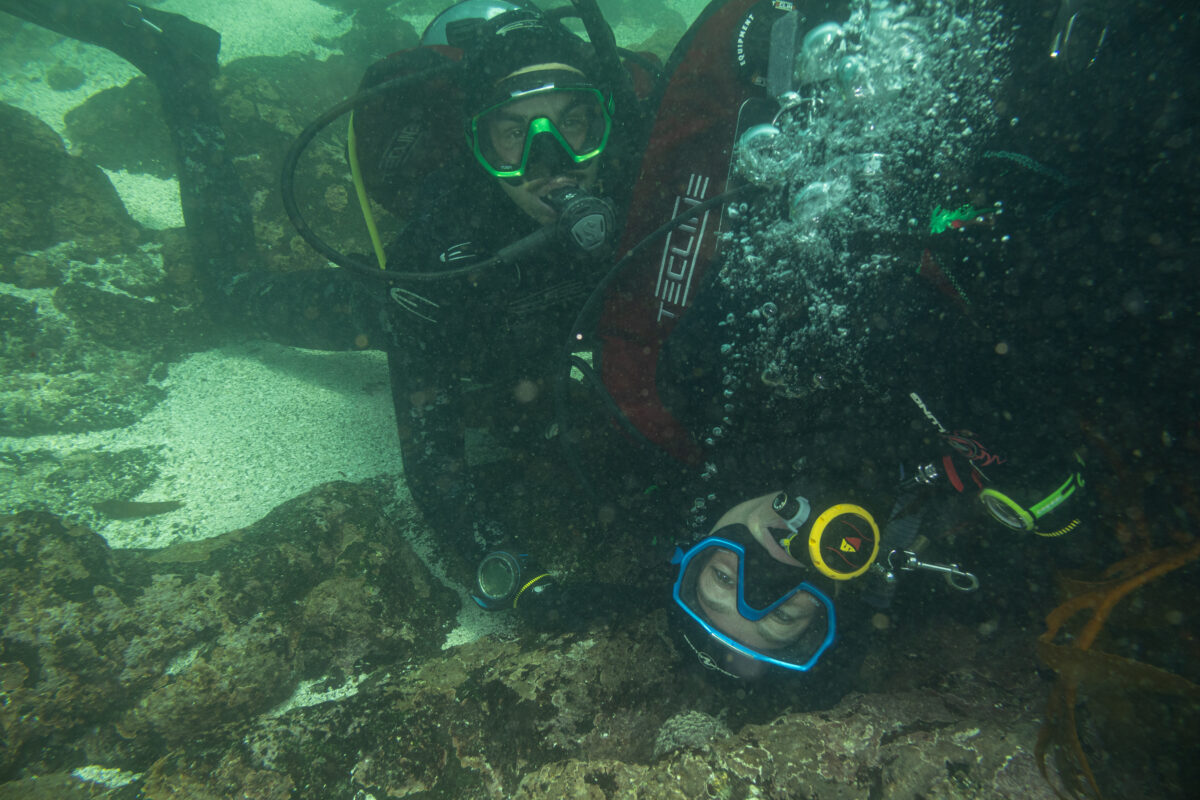

The Subelab focuses on understanding the ecology of fish and kelp, particularly how environmental processes shape their abundance and movement. A significant part of their research involves scuba diving, with fieldwork conducted in the cold waters of Chile. Wrapped in thick wetsuits and drysuits, the team braves the hostile environment regularly in the name of science.

I was lucky enough to join them on several dives, contributing to underwater surveys that mapped kelp forest ecosystems. They use Reef Life Survey methodology (an Australian-born technique) to assess the abundance, biomass, and distribution of kelp and the species that inhabit it along Chile’s central coast. I also assisted in surveys of fish and invertebrates, gaining hands-on experience in marine ecological research.

Beyond diving, Subelab is also pioneering acoustic telemetry research in Chile. They deployed only the second acoustic receiver array in the country’s history, tracking tagged fish and sharks to understand their small-scale movements for conservation purposes. This was particularly exciting for me, as I had used the same technology to study shark movements for my thesis last year.

This experience was a little more than just scientific work, it was also pretty personal. I was born in Chile, but left for New Zealand when I was just six months old. While I had returned a few times to visit family or travel, this felt different. I was working in my birth-country for the first time, immersing myself in its scientific community, meeting like-minded marine biologists, ecologists, and oceanographers. It was incredible to realise that my grandfather had once navigated these same seas with the Chilean navy, and now I was exploring them for conservation.

I am immensely grateful to the Subelab for welcoming me so warmly and making this experience unforgettable. I would love to return and continue collaborating in even bigger ways. This includes Alej, Gabi, Tomas, Cata-Ruz, Rodrigo, y mucho mas personas de ECIM. A heartfelt thank you to the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society for making this opportunity possible, and to all the supporting sponsors—Rolex, Tusa, Waterproof, Reef Photo and Video, and Fourth Element. Your generosity allows me to continue exploring and studying the underwater world. I am endlessly thankful for that support.