My next scholarship experience would take me to a remote island in the Philippines, Ticao Island, where I would be working alongside scientists and researchers from the Large Marine Vertebrate Research Institute Philippines, also known as LAMAVE.

Here I would spend the next month working as a research assistant with the diving team, a group of volunteer divers and scientists, who were led by Joshua Rambahiniarison, a Mobula expert in the Philippines.

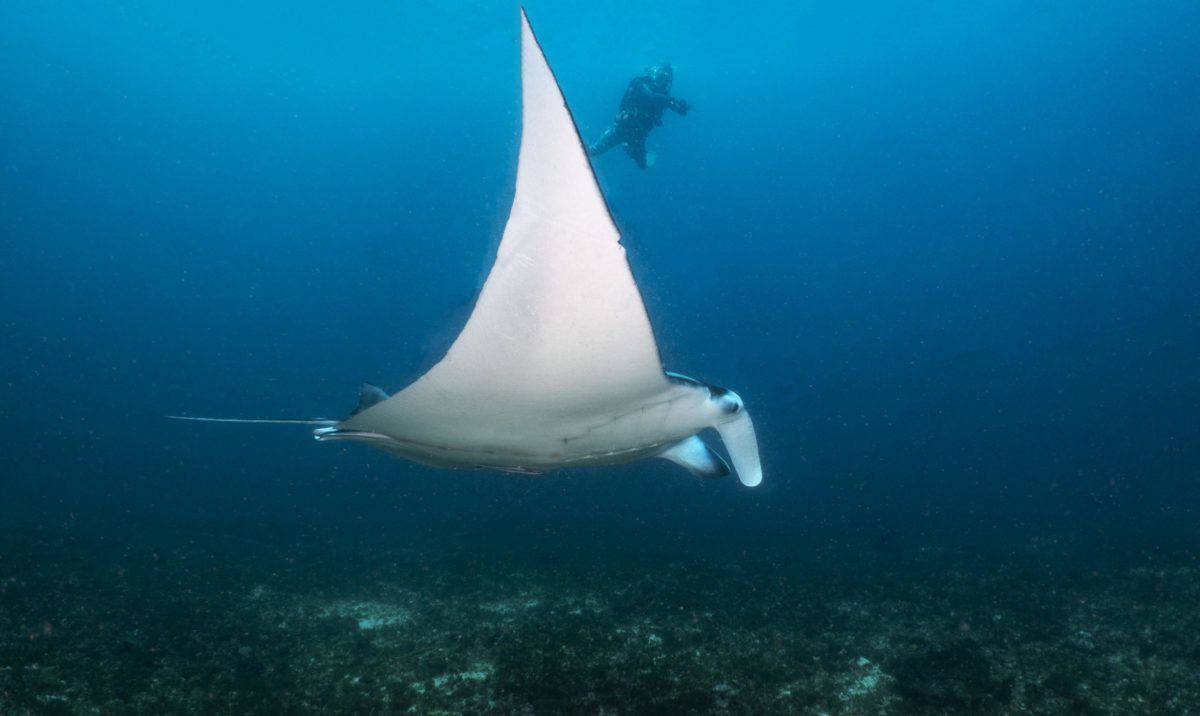

This opportunity would allow me hands-on diving research experience, where I would be assisting to undertake data collection in one of the most famous Manta Ray dive sites in the Philippines, Manta Bowl.

I was thrilled at the chance to immerse myself into a research project for a whole month, and particularly with Manta Rays! I had some previous experience with Manta Ray research when I worked in the Maldives as a Marine Biologist, so I was extremely excited to get back in the water with these magnificent animals, but also to be able to contribute to research.

Our research was based out of Ticao Island Resort, a resort that is flooded with guests each year to try and get the chance to dive with the amazing array of wildlife that passes through Ticao Pass (Masbate).

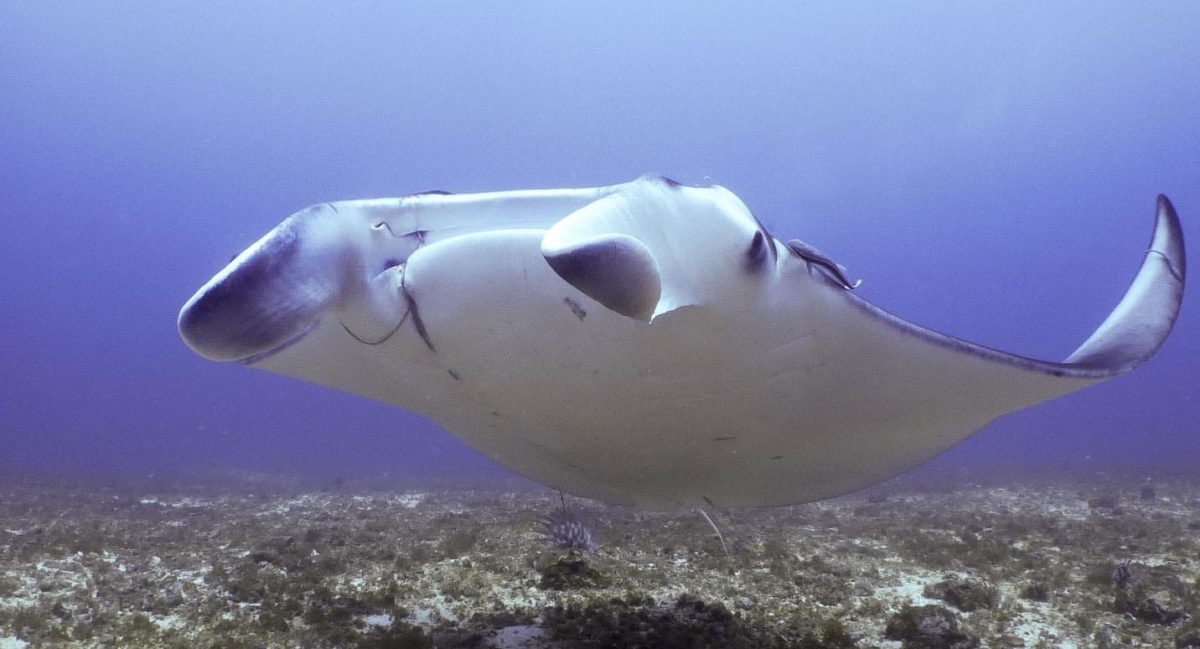

Off Ticao Island you can find Manta Bowl – this is a large seamount which has incredible habitat providing home to a diverse range of marine fauna. Manta Bowl provides a particularly important aggregating site and key habitat, essential for the ecology for both oceanic mantas, Mobula birostris, and reef mantas, Mobula alferdi. As well as habitat for Thresher Sharks, Whale Sharks, White-tip Reef Sharks and there have even been the occasional reports of Hammerheads and other devil ray species such as the spine tail devil ray (Mobula japanica) and the bent fins devil ray (Mobula thurstoni).

Manta Bowl is comprised of multiple reefs termed “cleaning stations”, which the Mantas visit daily in order to be cleaned by small cleaner wrasse. It is also a mating site, as well as a feeding area for these animals, further underlining the importance of this habitat. Currently, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the stock identity and the geographical range of these Manta Ray populations in the Philippines. However, despite the increasing diving tourism and the implementation of CITES and CMS Fishery Code, this site has only very recently fallen under the Burias-Ticao Pass Protected Seascape Act, as a Marine Protected Area. There is a need for more research to allow for strengthened convergence, collaboration, and cooperation between government and the multiple stakeholder groups who use the area in order to prevent future threats to the ray and shark populations.

The Manta Bowl project aims to collect a series of biological (manta photo identification by deploying remote underwater video), ecological (residency by using acoustic telemetry), environmental (current, food availability), and socio-economic (benefits generated by the manta diving tourism) data to be able to design a proper conservation and recovery strategy.

The management strategies will take local communities who fish in these areas and are dependent on this area into account. This data will set the basis for the creation of the first dedicated manta ray sanctuary in the Philippines.

During my month I was lucky enough to work with an amazing group of volunteers including Mika, Paul, Adam as well as Josh. We were up at the crack of dawn, heading out on a Banka, a traditional Philippine boat with the diving team at Ticao Island Resort to Manta Bowl.

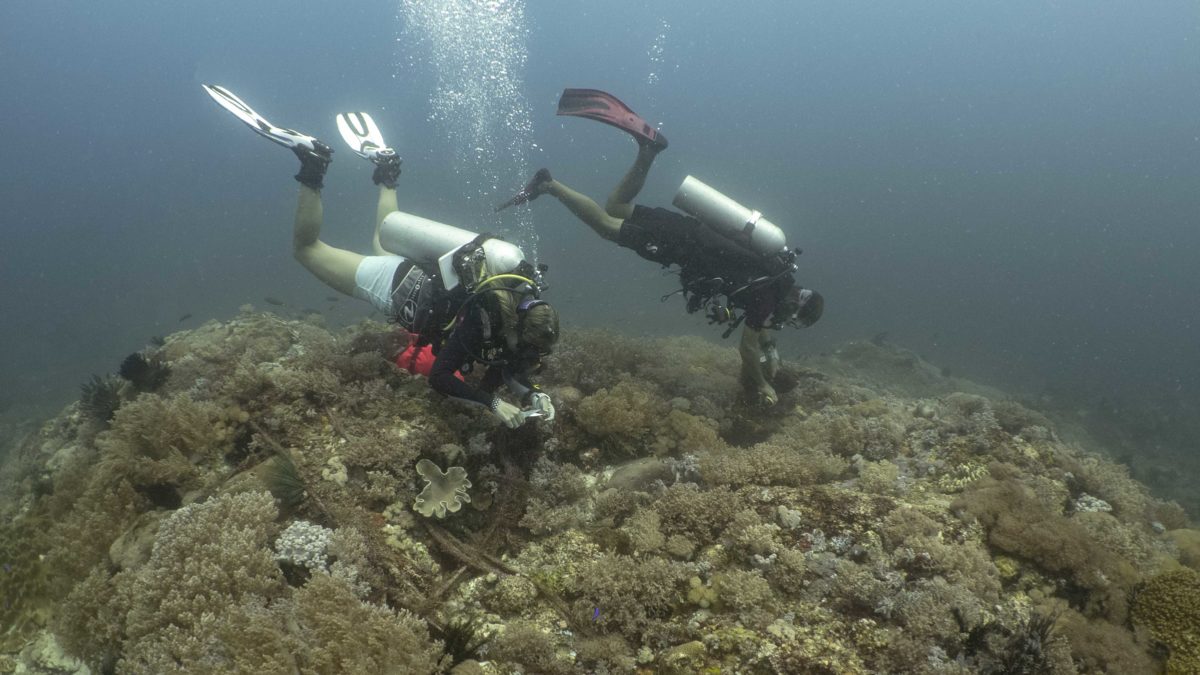

Our mornings consisted of retrieving and installing RUVs, also known as Remote Underwater Vehicles, throughout the Bowl, where they had been carefully placed to monitor the cleaning stations. In teams, we would be dropped right on top of the GPS location of the RUV site, and we would drop down to around 20m where the reefs were located. The currents were extremely strong, so it was important that we had our dive plan in place at the surface before we descended to the sites, which included Circus, Thandy’s Rock, Tamis, Pandy’s and Patches.

In teams, we would collect the RUV from the first site we had been dropped on, then would navigate our way to the next station, before surfacing. After being picked up by the boat we then would collect the data and do a battery swap and a camera re-set, before jumping in again to re-deploy the RUVs.

Every second day we would analyse the data we had collected from the cameras, which consisted of a series of time-lapse photographs of the manta bellies, which is a method used to identify individual manta rays. It is a bit like a human fingerprint, each manta has a unique individual pattern which gives us the opportunity to identify them. This then allowed a database catalogue to be built, so that we could start to learn more about the manta’s behaviour and how frequently they were visiting stations.

In the month that I was there, the catalogue grew by up to 50 new individuals! The growth of the catalogue was also facilitated with the help of guests that were staying at the resort, diving and taking photographs, providing a form of Citizen Science data to the database.

We also conducted a range of conservation work, including spending dives removing some of the many nets that covered the soft-coral reefs of Manta Bowl. This was a delicate task, as much of the fauna that inhabited these reefs had adapted to grow around the nets, so it required some attention to detail. We also encountered many mantas who unfortunately had fishing line entanglements, which when the opportunity arose, we very carefully attempted to remove it.

As well as the diving project, two other LAMAVE researchers including Executive Director, Jessica Labaja, and Project Leader, Sue Andrey Ong, were conducting a series of interviews with fisherman in each of the local villages. This side project aimed to gather a range of data from the local fishermen including on details such as what they catch and the types of methods they used to fish. This extremely important social data, particularly for those that are dependent on these reefs for their survival, will be taken into account for the assessment of the Bowl for future management.

The Manta Bowl project is aiming to identify and describe remaining populations of manta and devil rays in the country, identify conservation priority areas and migratory corridors. It is part of LAMAVE‘s efforts to conserve and restore Mobula populations in the Philippines. Through the collection of extremely important baseline data about the site, the most effective management and conservation decisions for the species will be able to be implemented. This will allow a basis to be set for the creation of a dedicated network of protected areas to hopefully allow the species a chance to recover.

By the end of the project, LAMAVE hope to be able to provide the local community and the local government with the tools they need to work together. This includes collaborating with other stakeholders to design conservation strategies and develop sustainable wildlife tourism.

This was an invaluable experience for me, to get hands-on diving research and conservation experience in a remote part of the world, as well as contribute to a fundamental study. Particularly a study that is endeavouring to provide the most effective management solutions for the wildlife, as well as the local communities who rely on the reefs for their survival.

I feel extremely lucky to have been able to contribute to a crucial baseline study that will hopefully result in the protection of an incredibly important habitat, for not only the mantas, but the many other species that use Manta Bowl. Being in such a remote part of the Philippines, really allows one to appreciate the importance of these reefs for these small communities, and how in order to protect them, scientists and government need to work with the locals for the most effective outcomes.

I can’t thank the LAMAVE team enough, particularly Josh, Mika, Jess, Sue, Adam, Paul and Sally for my time with them, and I could not recommend this experience more to those that are seeking hands-on research opportunity. Next, I’m heading back to Australia where I will be undertaking my PADI Instructor Development Course with Dive Centre Manly in Sydney.

A big thank you to those who continually support my scholarship year: OWUSS, Rolex, TUSA, Waterproof International, DAN, PADI, Mako Eyewear, Reef Photo & Video and Nauticam.