Nearly 50 years ago, Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions became the first shark tour operator in the world. Today, shark diving and ecotourism is a huge, growing industry around the world, contributing widely to a greater public appreciation of these animals. Established in 2001 by Rodney and Andrew Fox, and shark scientist Dr. Rachel Robins, the Fox Shark Research Foundation was formed alongside the expeditions to take this one step further, utilising the unique opportunity to get up close and personal with Great White Sharks to research and learn more about them.

Despite the high profile media attention that the Great White Shark receives, relatively little is known about its life history and ecology, and there still remains much to be discovered and understood. As a live-aboard operation, RFSE offers a unique platform for visiting researchers and scientists to study White Sharks, an otherwise very elusive animal. Since it’s establishment, the Fox Shark Research Foundation has been involved in a wide variety of research projects and data collection initiatives, using a range of technologies in tagging and photo identification to track and study behaviour and population trends of the great white sharks of South Australia.

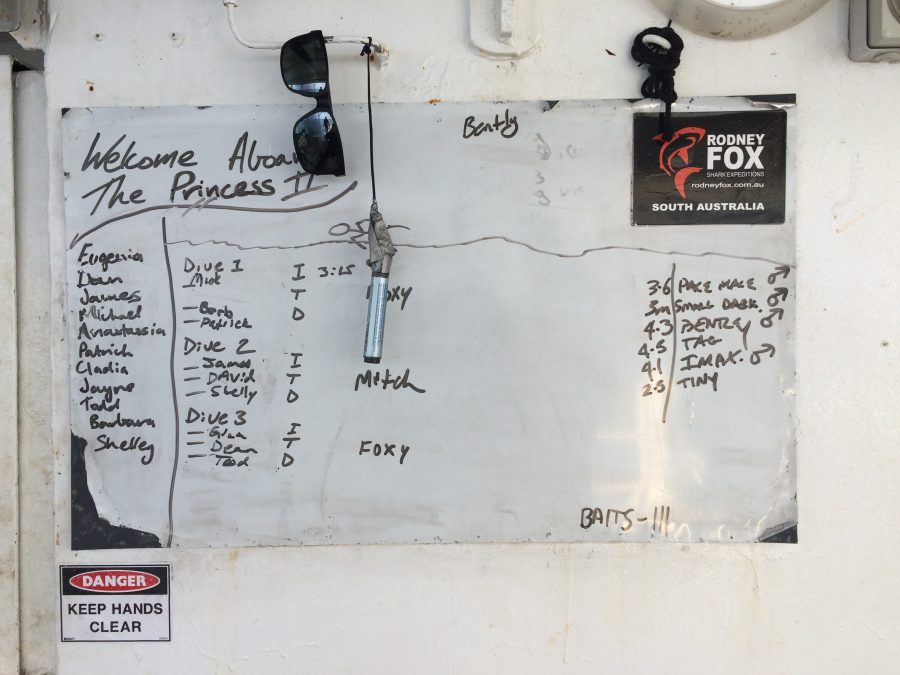

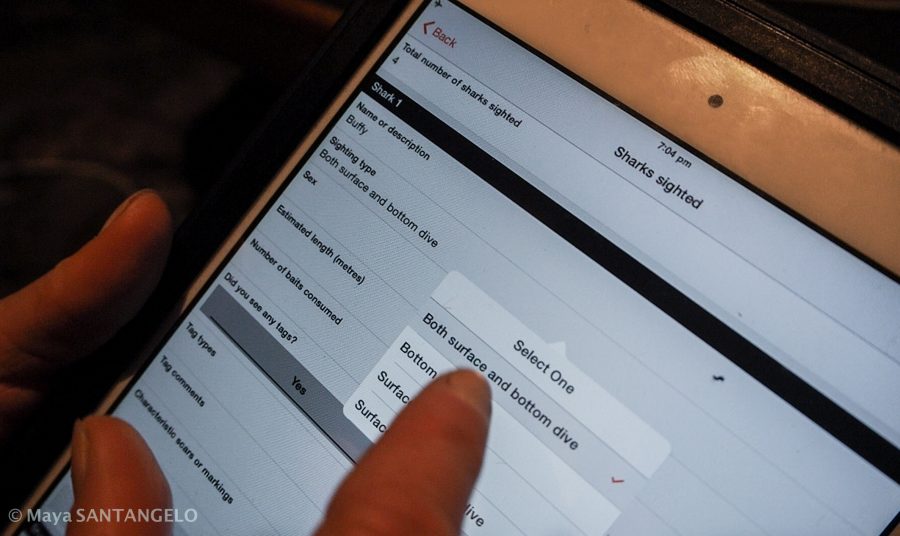

Each day out at the Neptune Islands is a chance to learn something new about the sharks. On board the Princess II, the RFSE crew keep track of the individual sharks sighted throughout the day, giving an idea of what individuals are resident or visiting at a given time. Observations of individual sharks are recorded daily, including information such as previously identified or new individuals, sex, size, any distinct markings or tags, as well as where they were seen and if any bait was eaten.

This information is collected in a survey program to work closely with the local government and the CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) as a way to monitor white sharks visiting the cage diving operations at the Neptune Islands.

While working with the crew of RFSE, I was able to contribute to the daily shark observations and monitoring by collecting photos and video footage of the sharks, to help identify and clarify any individual sharks seen on a given day. After quickly appreciating just how difficult it can be to actually capture a clean profile of the length of the shark in one shot, unobstructed by the hoards of silver trevally, I learned what physical features are key for identification purposes.

While some of the markings seen on the sharks are only superficial and temporary, such as scars from interactions with prey (seals) or other sharks (particularly during mating time), ideal features to use to identify the sharks are those that are less likely to change over time. Features such as the countershading boundary markings along the side of the shark, particularly around the gills and lower caudal fin area, as well as obvious shapes or amputations of fins are distinct and unique patterns (and some of Andrew’s favorites) to identify the sharks and profile them for the life of the individual as long as they are seen at the Neptunes.

Over the years of building an extensive photo ID library of resident and visiting individual sharks at the Neptune Islands, the expert knowledge and understanding of the team led by Andrew Fox allows for recognition of the individual sharks in the area. Being able to recognize (and know by name!) hundreds of individuals is a huge advantage when it comes to knowing exactly which sharks they are subjecting to and dealing with for research purposes. This is particularly useful in research studies utilizing tagging and bio-sampling technologies, for example when an individual of specific age or sex is required to investigate certain aspects of white shark ecology or life history.

During my time on board RFSE, I was fortunate to be part of an 8-day shark conservation and research focused expedition with visiting conservation group, Fins Attached. Arriving excited and prepared with three satellite tags, the goal of the trip was to deploy these tags onto mature female white sharks found at the Neptune Islands.

Tagging technologies commonly used to study sharks and other marine animals include acoustic and satellite types. Each have their own benefits and limitations – acoustic tags are cheaper and widely used, but only record information on a presence/absence basis when the tagged animal is within proximity to an acoustic receiver, while satellite tags record much more detailed information about the exact movement patterns of the animal, as well as about depth and temperature, over the lifespan of the tag, but at a greater financial cost. Data collected by tags can be incredibly valuable in providing essential information to answer questions and mysteries to understand animal movements, habits and critical habitats in their life history, such as feeding or breeding grounds.

With the goal of deploying satellite tags specifically onto sexually mature female white sharks found at the Neptune Islands, the Fins Attached conservation group would therefore be able to contribute greatly to our understanding of where white sharks may go to mate and breed, once they have left the feeding grounds of the Neptunes. Thanks to the knowledge and recognition of the individual sharks by Andrew Fox, we were able to know whether the sharks we were encountering on this 8 day expedition where viable options for investigating these questions and deploying these tags. Excited at the opportunity to contribute to white shark science, we made our way to the Neptune Islands, ready to look for the super giant female white sharks regularly visiting in winter.

Often the way when it comes to achieving science goals, however, nature has a convenient habit of getting in the way. While the Neptune Islands are home to white sharks throughout the year, with larger, mature females seen in the winter months, so far this winter season we were yet to be graced with the presence of these super giant girls. Female white sharks reach sexual maturity at about an average age of 15 years, requiring us to have access to individuals of at least 5m in size to successfully deploy tags for the purpose of investigating their life habits and movements around times of mating and breeding. Over the course of the 8 day expedition, the largest female shark we had was a submarine beauty by the name of Buffy. Although just over the 4.5m mark in size, Buffy was not quite large enough to deploy a tag for this particular goal.

With luck of eligible sized shark bachelorettes not quite on our side, our goals shifted to make the most of the expedition, taking the opportunity to learn more about some of the local shark science going on through Flinders University of South Australia. Joining as on-board shark scientist, PhD student Lauren Meyer is investigating the effects of the cage diving industry on the ecophysiology of white sharks and on the structure of local ecosystems of the Neptune Islands.

The use of bait and berley by the shark diving industry can be a controversial topic, despite the opportunities it offers to be able to observe an elusive animal for research purposes and shifting public attitudes and appreciation. While the white sharks naturally aggregate around the Neptune Islands to feed on the resident seal colonies, they are drawn to the boat through the use of bait and berley. When observing the sharks, we try our best to ensure they are not actually feeding on the bait, by pulling it away from incoming sharks. Of course this can be harder on some occasions than others, and sometimes the sharks do get the bait. Lauren’s research is therefore trying to answer the question of whether the sharks are changing what they eat from blubbery seals to fish used for bait, as a result of the presence of cage-diving industry in the Neptune Islands.

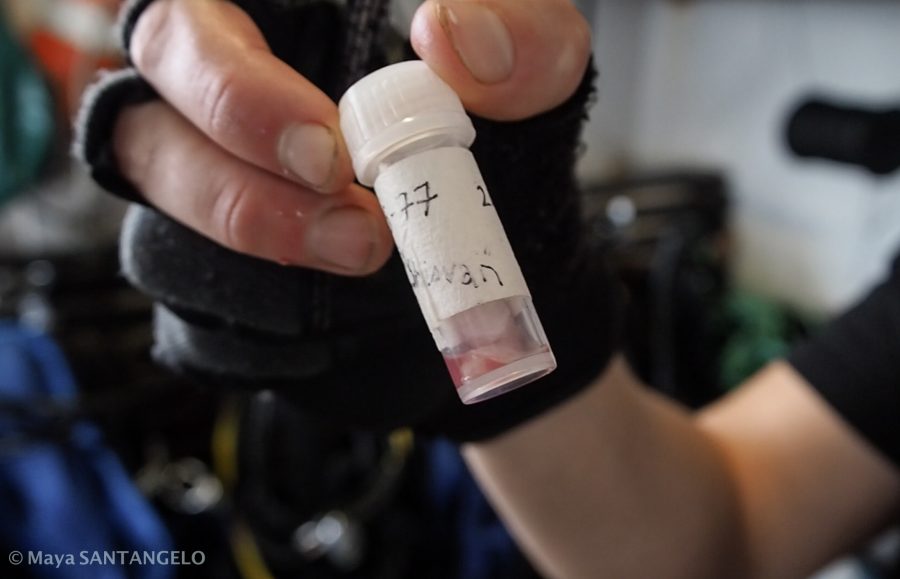

With standard techniques of assessing feeding ecology, such as stomach content analysis, out of the question for a threatened species, Lauren’s research is using a biochemical approach and new techniques to answer these questions. Lauren’s study involves analyzing fatty acid profiles of small muscle biopsies taken from sharks swimming past the cages, which reveal critical information about the sharks’ diets and feeding ecology. To obtain a clear picture of the diet of the sharks during their time spent at the Neptune Islands, Lauren obtains biopsy “before and after shots”, which allow comparison of what the sharks are eating before arrival at the Neptune Islands, and what the sharks have been eating since staying at the Neptunes for the winter season. To learn more about Lauren’s research, have a read here.

Over the multiple days spent at the Neptune Islands, Lauren was able to obtain a few successful shark biopsies for her research. Using a modified spear gun, Lauren collected a small muscle and tissue sample from the flank of a sub-adult male passing by the bottom cage. What was originally thought to be a “before shot” of a new individual, later cross checking of footage and photos showed that it was in fact a very useful “after shot” of a shark she had previously biopsied.

Having already collected “before shots” from a few different individuals, Lauren was hoping to obtain “after shot” biopsies from these specific sharks on this trip. On one of the last days, with her gear prepared for the day and lovely calm conditions at the surface, we were graced by the presence of a large female white shark by the name of Shiovan. Cruising past the surface cage at the back of the boat, Lauren was able to collect a biopsy from the marlin board at the last second before Shiovan dived back to the depths. A very exciting and important “after shot” biopsy for her study, we were all stoked to end the trip on a successful note.

As imperative as it is to assess what is happening directly to the white sharks, it is equally important to determine what is happening to the other marine life that make up the diverse ecosystems of the Neptune Islands. Lauren is therefore also using biochemical tools and Baited Remote Underwater Video Surveys (BRUVS) to find out if and how the cage diving industry may be affecting the diets of the fish, rays and other animals commonly aggregating around the tour operations. You can also learn more about this aspect of research here. Data revealed from these studies are critical in not only developing our understanding of the lives of white sharks, but also how our actions in the diving industry are effecting their ecosystems, and will help us to develop and enforce appropriate management and policy to ensure the cage diving industry continues as sustainably as possible.

From a scientific perspective, there are still many mysteries to be discovered and understood about the Great White Shark, and the team at RFSE are continually working to help find answers to some of the most intriguing questions. I cannot thank Andrew Fox and the entire team of passionate crew of Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions that I was lucky to spend time with – Bec, Rory, Mitch, Mike, Dani, Lauren, Kristi, Jade, and skippers Shawn, Jeff and Wayne – enough for making this experience so rewarding. I had so much fun getting to work with and learn from you all, and I can’t wait to see what you all help discover about these incredible sharks next!